Snapshots from our pilot analysis: What’s behind conflict stakeholders’ positions?

Published: 19 August 2020

Author: Andreas Hirblinger

When leveraging the potential of machine learning (ML) tools for peace mediation, we are particularly interested in applications that enable meaningful analysis of unstructured text-data. Many available applications – including sentiment analysis – have their origins in for-profit use cases, and particularly, the advertisement industry. These tools may be well suited for automated tasks of analysis that help assessing and categorizing online users’ preference for/against specific products. In peace processes, sentiment analysis tools could prove helpful when wanting to get a sense of the subjective stances that exist in regard to a specific aspect of a possible agreement. This could advance the “marketing” of specific solutions – but usually, mediators don’t have one readily available. This begs the questionhow ML tools could be used at a stage when the “product” (i.e. a solution to a contested issue) hasn’t yet been developed.

Conflict parties and their constituents maintain a complex set of considerations in relation to every single issue of contention. Many of these thoughts may be implicit and informal, which makes them not readily crawlable by off-the-shelf social media analysis tools. It is therefore important to analyse conflict parties’ reasoning in a fashion that is both more inductive and more able to capture the complexity of reasoning processes, which underpin any given position. Such efforts may be especially worthwhile in early phases of mediation, to better understand what’s “below” conflict parties’ positions and interests, but they can benefit later stages as well, since conflict party positions continue to change.

We recently conducted a range of data analysis pilots, in order to get a better sense of what kind of information can be extracted from various data types, such as social media data, survey data, and transcripts of parliamentary debates. In the course of the exercise, we collected data for several hypothetical peace mediation scenarios, to identify positions and arguments around a specific issue of contention that could be brought to the negotiation table. Using a simple coding framework, we annotated positions, as well as the premises and conclusions, which these were based on (intermediate conclusions that served as the basis for another conclusion were coded as conclusion-premise). Our exercises indicate that these data sources have much more information to offer than what can currently be assessed with existing ML techniques – the data quality also differs depending on the source and collection method.

India: Debating the Citizenship Amendment Act

A preferable source for studying arguments are parliamentary debates, because they usually contain relatively well-developed premises and conclusions. However, in many conflict-affected contexts, parliaments are ill-functioning, don’t have a sufficiently open debating culture that allows for free speech, or don’t transcribe, archive and publish speaker transcripts. Although this data is often not available, in cases where theycanbe accessed, transcripts of parliamentary debates may provide a suitable source to analyze arguments relevant to topics and issues of contention relevant for peacemaking.

In India, for instance, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which was introduced in December 2019and ratified in parliament, led to widespread protests among Muslims and other religious minorities. Those against the law andits associated proposals, like the National Register of Citizens (NRC),argue that the CAA is an attack on the country’s secular system and an attempt from the Modi-led government to turn India into a Hindu-centric state. The protests that were initially peaceful escalated in January, when the authorities shut down internet and phone services. The police have also been criticized for using excessive violence against those protesting for a repeal of the bill, which has sparked social media outcry.

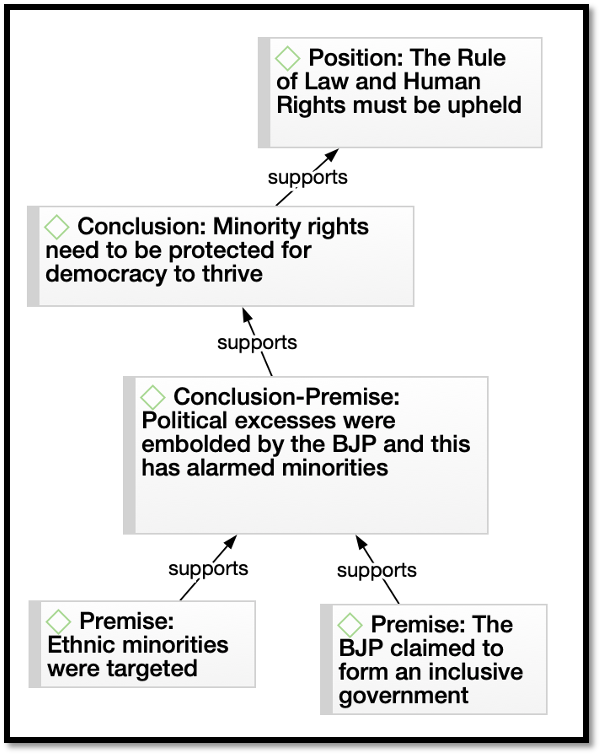

Searching transcripts of the debates of India’s parliament, the Lok Shaba (House of the People), for relevant keywords – we identified relevant argumentative units, from speakers’ comments on the CAA and the political unrest that followed suit. A manual analysis of these units helped to determine specific positions in relation to the bill, as well as the premises and conclusions that underpin these. One Member of Parliament argued for instance that:

“BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) gave the slogan of 'Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas', of forming a Government aimed at working for the masses, inclusive of all castes and communities. But the overt, majoritarian excesses that became emboldened by the BJP Government have sent alarm bells off among the minorities. During these five years, more than 100 Dalits and Muslims were lynched by mobs in India on suspicion of slaughtering cows. For a democracy to thrive, it must be underpinned by the rule of law and protection of human rights.”

This relatively complex argument can be broken down into various premises and conclusions, which finally support the speaker’s position, namely that the rule of law and the protection of human rights must be upheld, as visualized in this simple argument network:

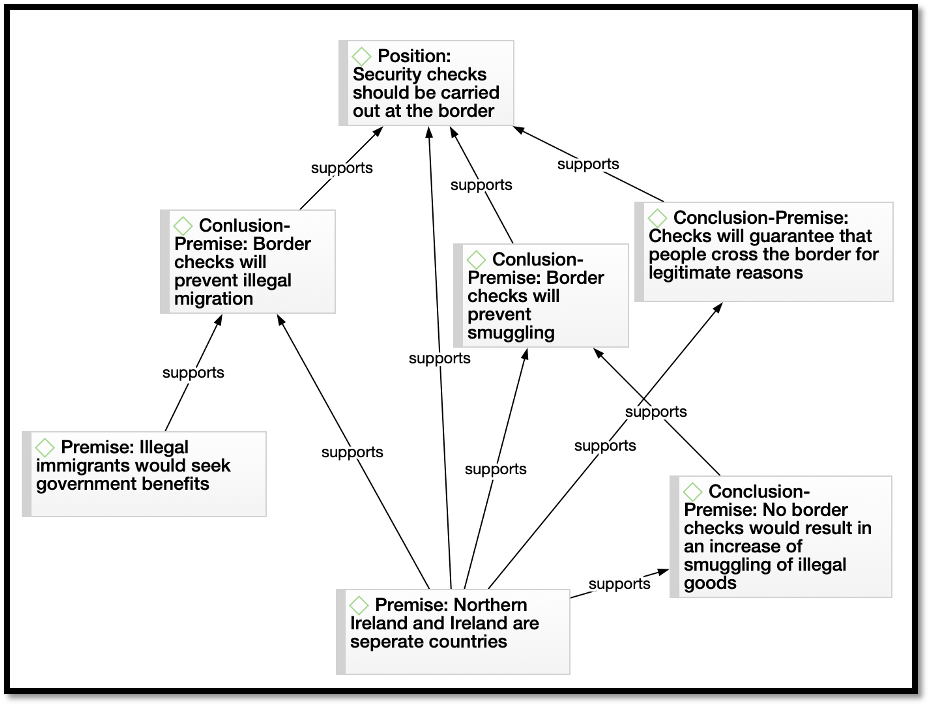

Northern Ireland: Border problems post-Brexit

In Northern Ireland, Brexit opened up the for the possibility of a “hard” border between Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom (UK). This triggered concerns about the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) that was signed in 1998, which created new institutions for cross-border cooperation between the British and the Irish government. There’s a fear that the conflict which was fought between protestant “Unionists” (in alliance with the UK) and catholic nationalists (who sided with Ireland – including the paramilitary group Irish Republican Army (IRA)) will resurrect. Brexit has raised questions about the future for border management on the island in order to sustain peace. In an online survey, we asked how the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland should be managed in the future, and why the suggested steps would be the best option. The example below displays the argumentative structure that underpins one of the respondent’s position, in favor of introducing security checks at the border. The respondent stated that:

“I think there should be security checks carried out on the border to search cars etc leaving either country to stop items being brought into either country that shouldn't be. Passports or other forms of ID should be asked for at the border and checked to make sure people are who they say they are.”

To justify this response, they further elaborated:

“As it’s two separate countries there needs to be checks on the border to stop things being smuggled between the two. If there were no checks, I think we could see an increase of weapons, drugs etc being transported over the border between the two countries. Doing checks could prove people's identities and ensure people are crossing country for legitimate reasons. It would also help to check lorries for illegal immigrants and put a stop to them before we end up with a load more immigrants seeking government benefits etc and a home to live. The two countries simply need treated as two different countries because that's what they are.”

Let’s assume for a moment that this argumentative pattern could be identified across a large number of respondents, and that it relates to a specific conflict party constituency. It would then be clear that this constituency is concerned with risks of increased smuggling and illegal immigration, with their claims based on the premise that Northern Ireland and Ireland are two separate countries. As border checkpoints would violate the GFA provision for the removal of security installations along the border, knowing about the deeper concerns about smuggling or immigration may enable the mediator to inject alternative proposals that could address the stakeholder groups’ concerns.

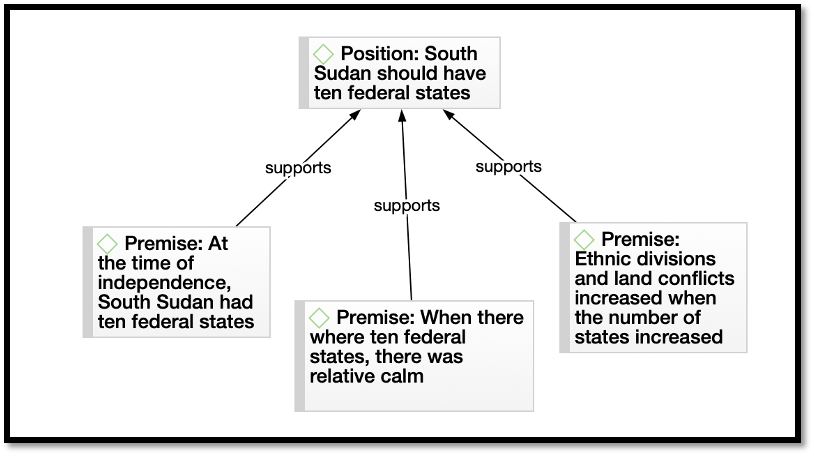

South Sudan: How many federal states?

In South Sudan, where a civil war has engulfed the country since December 2013, a pivotal issue of contention between the conflict parties has been the number of federal states. After the country’s secession from Sudan in 2011, South Sudan was divided into ten administrative states. During the conflict, the main armed opposition groupSPLM-IO demandedthat the country should be composed of 21 states instead.Since then, theruling President Salva Kiir, has increased this number to be 28 and later 32 states. Many see these changes as the President attempting to consolidate his power, through the creation of states in which his government could achieve an electoral majority. Others argue that the politics around the number of states, have to do with natural resource availability, ethnic claims to land, or narratives about national unity and diversity.

For this case, we asked survey respondents how many states they think South Sudan should have, as well as explain why their option would be the best solution to the conflict. One of the respondents argued for a return to ten states, explaining that:

“This is the best solution because when the country became independent, it seceded with ten states and there was relative calm with the ten states, there was no ethnic division and land conflicts as was observed when the states were increased.”

Yet, South Sudan was challenged by ethnic violence and land conflicts before the civil war outbreak in 2013, and these dynamics of violence cannot be easily addressed by simply changing the number of federal states. If this thinking would be representative for a larger stakeholder group, mediators could use such an analysis to redirect the discussion to some of the more complex problems of South Sudan’s ongoing crisis – including questions of national identity and land rights.

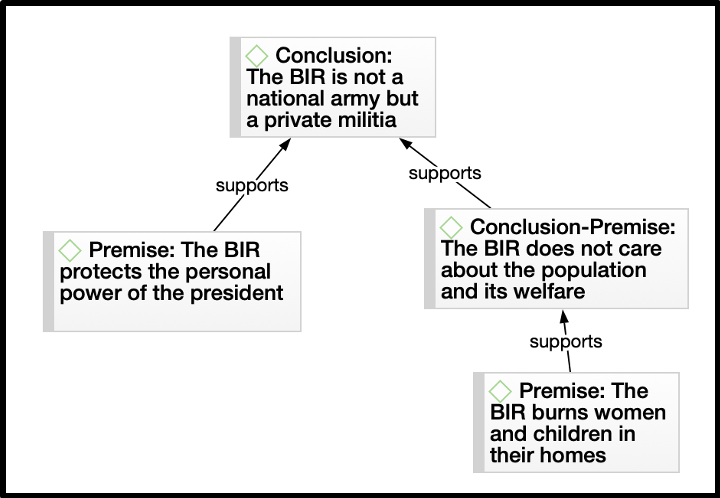

Cameroon: How violence against civilians reduces the Army’s legitimacy

A bigger challenge in harnessing ML tools for peacemaking lies in the reconstruction of positions and arguments from social media. Using Twitter data, we screened for Tweets with relevant content to the current political crisis and armed uprising in Cameroon.Over the last years, the country has seen a surge of violence, caused by intensified tensions between its Francophone and Anglophone populations. The latest wave of hostilities dates back to 2016, when Anglophone teachers and lawyers took to the streets to protest against the Francophone-dominated government’s imposition of French onto their regions. What started out as peaceful protests, was met with violent pushback from the state. This response radicalized parts of the protest movement into a secessionist group, which announced the independent state of “Ambazonia”in 2017. Social media has played an important role in spreading awareness on Anglophone secessionism as well as been useful in coordinating protests and boycotts against the government.

On Twitter, arguments are often abbreviated and incomplete, and relevant information may be “hidden” in hashtags or other Tweets, with which the user engages. Reconstructing arguments is less straightforward and therefore possibly less rewarding. Tweets may nonetheless help to compare how arguments differ online and offline. Mediators may be able to identify specific social mediainfluencersthat shape online narratives which come to impact offline political processes. Twitter could for instance be used to delegitimize other conflict parties and their actions. One user argued:

“Stopcalling the BIR,‘Cameroon's Army’–it's a dictator's private Militia to protect his power. That's why they don't care about the population and their welfare. According to them they can continue burning Women and Children in their homes, nobody cares after all.”

A reconstruction of the Tweet suggests that this stakeholder believes that the Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR) – which formally is a part of the Cameroonian Army – are targeting and harming civilians. The Tweet further outlines that the Army doesn’t care about the population, but is instead preoccupied with upholding the power of President Paul Biya. If comparable arguments would emerge among a whole constituency, this would provide important insights into why the Anglophone secessionist movement views the BIR, a conflict party rather than as part of a national army that would protect the whole of the population. In order for this perspective to change, attacks against civilians would have to stop.

Automating analysis: Paving the way to participatory peacemaking?

When automating argument analysis to systematically review large amounts of data, several aspects will have to be considered. For instance, what data type to draw on depends on the objective of the analysis: Do we want to get a sense of the reasoning of political elites and high-level decision makers? – Then analyzing parliamentary debates, official statements and press releases may be in order. Or would we like to understand how arguments form and travel on social media? – Then Twitter will be the right data source. For many other tasks however, analyzing data that is actively generated during digital inclusion activities – such as through surveys or during online focus groups – might be the most promising. This not only allows to gain better information about the “users” behind the data or to control the respondent group, but it can also enable forms of participatory analysis. In this case, a joint interpretation of data can become an important part of the peacemaking effort.